Porting/Optimizing HPC for ARM - A Definitive Guide

High Performance Computing (aka HPC) software often refers to software/application that needs significant computing power. Examples include database servers, application servers, big-data applications, etc.. Operation is not only limited to data processing but also involves heavy IO to the different channels. The software needs to ensure optimal overlap of CPU workload and IO workload keeping CPU busy while the next set of the data to process is being loaded by IO sub-system.

At first look it may sound simple but ensuring the optimal performance with increasing scalability makes it challenging and fine tuning such a system to work universally for different workloads further makes it complex.

ARM and HPC

ARM processors are widely used in low-power consuming devices like cell-phones, home-appliances, specialized devices, etc… ARM processor’s less power consumption and optimal cost, made it a best possible choice for the application that needs longer battery life. Few years back a completely new vertical of using ARM for HPC started gaining pace. With a single core/CPU reaching the scalability threshold the only way to scale CPU (for more compute power) was to add more cores. ARM processors perfectly fit this paradigm and with the software adapting to this multi-core model, it helped fulfill compute power demand too.

No surprise world fastest supercomputer is based on ARM processors with 7.3 millions cores.

What further fueled use of ARM for HPC is the introduction of ARM instances on cloud. With the majority of the desktop machine still powered by x86 developing an application for ARM was a bit of challenge but with easy availability of ARM based processors through cloud instances made it an ideal choice for developers to port software for ARM and users to run it on ARM.

ARM has been constantly gaining popularity to run HPC software supported by a continuously evolving software ecosystem. Most of the OS now provides ports for ARM along with respective packages. Majority of the software vendors (including HPC) have already ported their softwares (or in the process of porting) to ARM with regular releases. In the database world itself some of the popular software like MySQL, Postgres, MariaDB, AWS-RDS, etc… are available on ARM.

Cloud provider providing ARM based instances:

- Huawei Cloud provides ARM instances powered by Kunpeng 920

- Amazon Cloud providers ARM instances powered by Graviton 2

- Oracle Cloud plans to provide ARM instances powered by Ampere Altra.

- As per report Microsoft is also working on ARM chip.

In addition, the introduction of Apple M1 gets a decent power ARM processor to the desktop. Lot of other vendors too provide ARM based desktop that too is slowly gaining pace.

Running vs Optimizing HPC on ARM

ARM is little endian and porting existing software to ARM should be pretty simple. Software based on JDK or Python should just run out of box as both the interpreters are available on ARM. C/C++ based software too will run on ARM (with packages built for ARM or users could also compile software on their own as gcc/clang are available on ARM).

So where is the catch? Software that works optimally on other little endian systems (say x86) may fail to scale on ARM. So there is a difference when we say something runs on ARM vs something is optimized for ARM. ARM is a different processor so some of the lower level code needs to be re-optimized. Also, ARM processors tend to have more cores (in turn more numa nodes) so software may need to adapt to it and explore massive parallelism but limiting cross numa data movement. Lot of such things need to be cared about to make software optimal for ARM.

Given this background let’s identify some important generic points that could help optimize any software for ARM.

Optimizing software for ARM

1. Memory Model

ARM has a weaker memory model thereby allowing more flexibility of re-ordering instructions both during compiling and execution level. x86 has a strong memory model. This memory model difference can limit how efficiently a processor could execute/pipeline the code.

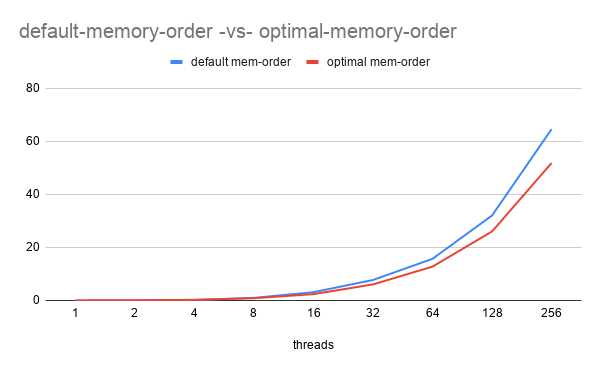

Programming languages like C/C++ define memory models thereby allowing users to specify the optimal memory order rather than relying on default which is mostly sequentially consistent. Default memory order may work fine for x86 but for ARM ensuring a proper memory order is important for optimal throughput.

Let’s understand this with an simple example:

- LOAD operation should generally use acquire-barrier (ensuring no follow-up instruction is re-order before the load).

- STORE operation should generally use a release-barrier (ensuring no preceding instruction is re-order after the store).

- An atomic counter (not meant for any holding state information) should use a relaxed memory barrier.

From the above graph it is clearly seen that using optimal memory order helps reduce the execution time improving performance/throughput. Sample program could be found here.

#ifdef OPTIMIZED

x.compare_exchange_strong(e, false, std::memory_order_acquire, std::memory_order_acquire);

ops.fetch_add(1, std::memory_order_relaxed);

#else

x.compare_exchange_strong(e, false);

ops.fetch_add(1);

#endif

Generally, most of the software started using atomics but ignored the memory order given it was not that important from an x86 perspective but with ARM it could have a significant impact.

Take-away:

Re-examine/study all the atomic memory orders and switch them to use optimal memory barriers based on the flow. It is also recommended approach as it helps clarify the intention of the developer and immediately helps clear the flow semantics for new developers looking at the code.

2. Low Level Code optimization

Certain operations are frequently invoked by the program so in order to improve efficiency it is normal practice to use an assembly level construct of the code as it may involve accessing low level CPU registers. Examples: timer operation, spin-loop operation, etc… Parallel code construct should be added for ARM using ARM specific assembly instruction.

ARM assembly based timer-access

{

ulonglong result;

__asm __volatile__("mrs %[rt],cntvct_el0" : [ rt ] "=r"(result));

return result;

}

Spin-Loop often involves active sleep (better known as pause). x86 has a direct assembly instruction named PAUSE. ARM doesn’t have PAUSE instruction but close resemblance is yield which tends to have varying semantics. Often introducing a notional delay without cpu-core switchover could be done using some instruction that consumes X cycles. More like an operation not meant to do anything meaningful just actively waste some CPU cycles.

There are multiple variants of this spin-loop pause in ARM

__asm__ __volatile__("" ::: "memory")

__asm__ __volatile__("isb" ::: "memory")

__asm__ __volatile__("yield" ::: "memory")

atomic_compare_and_exchange(expected, oldval, newval)

It is often recommended to try out different variants and adapt the one that best works for given software. Hopefully, in future, yield semantics would improve or an independent PAUSE instruction would be introduced.

3. More cores/More Numa Nodes

Most of the ARM processors are designed to offer more cores that in turns get more numa nodes. Cross NUMA latency is higher (n0 -> n3 = 33 units vs n0 -> n1 = 16 units). Ideally, core and memory should be co-located so there is no cross-numa migration of data or core re-scheduling but this may turn out to be optimal as it introduces heavy restrictions on scheduling and also practically co-locating data may not work always.

This could be optimized using multiple techniques:

- Larger chunk of data holding memory should be uniformly interleaved among the numa nodes. If a machine has 4 numa nodes and software tends to allocate 100 GB then ideal allocation would be 25 GB per numa node (assuming cores from all the nodes are being used). Explore setting it externally using numactl (numactl –interleave=0,1,2,3) or internally using syscall

set_mempolicysyscall. - Often software would have a global memory area that holds some global counters or global state variables. This introduces 2 main challenges:

- Increased contention: Being global it is likely that all cores will access it there-by increasing contention.

- Cross-NUMA movement: Each core will have to load it in its L1 cache. This means the said memory/cache line needs to migrate to the respective core numa node when it is accessed.

Both of these issues could be resolved by switching to a distributed counter where-in each counter is divided into N parts (say 1 part per core) and each core updates its respective part. Aggregate value of the counter is obtained by summing up the parts. This help resolve both the issues:

- Since each core accesses its own part lesser/no contention.

- Since each core accesses its own part the said cache line would be local to the core (no numa movement)

There is no concept of core bind memory and different threads may get scheduled on the same core so often a core affinity (in form of core-id) is used to select a part from a given N parts. Simplest way to get core affinity is using sched_getcpu. Latency of obtaining core-id shouldn’t circumvent the saving from cross memory access. On some ARM processors, sched_getcpu tends to have higher cost so a random counter based on timer or other unique features could be used.

Idea is to limit cross numa access or lesser contention should be explored across the board (not limiting only to the counters). For example for state variables instead of using old style lock-update-unlock (lock based solution), lock-free solutions could be explored through atomics.

4. Cacheline Differences

In point (3) we touch on the concept of accessing global memory counters. There could be more than one counter defined one after another and that means 2 or more counters could share the same cache line. CacheLine is the minimum memory that core needs to load to its L1/L2/L3 cache for accessing the said memory location. Assuming the core needs to update the single counter from the given cache line and another core needs to update another counter but located on the same cache line. In theory, there shouldn’t be any contention but in practicality there is contention since both share the same cache line and only 1 core could have exclusive access to the said cache line.

This is resolved by aligning/padding some of the hot-global-counters to cache line size. This will ensure the counter doesn’t share a cache line with another counter.

It is quite likely, software would have cache line alignment (or padding which is common with traditional software) but given that ARM processors have a wider cache line, ensuring that the alignment or padding is tuned as per said processor is important. For example: Most of the ARM processors tend to have 128 bytes cache lines. Of-course this is not standard and each L* cache level could have different cache line sizes too. Wider cache lines would still work for processors with smaller cache lines but not vice-versa.

5. Branching/Pipeline Differences

Software is filled with branching conditions. Most of these conditions don’t make a major difference on performance as new-gen processors are smart enough to amortize their evaluation cost but what if the given loop/condition works optimally on X architecture but fails to perform the same way due to branching and pipeline logic that is often beyond direct software control.

Profiling should help identify if the given loop/branching is turning to be costly and accordingly hints could be passed to the compiler so that compiler could generate code differently ensuring most opted branch path is optimally served.

Let’s take a simple spin-lock example that tries to spin if the lock is not available.

void lock()

{

while (true) {

bool expected = false;

if (unlikely(!lock_unit.compare_exchange_strong(expected, true))) {

__asm__ __volatile__("" ::: "memory");

continue;

}

break;

}

}

unlikely()

Elapsed time: 40.1403 s

86.09 │48:┌──b.eq 54

9.27 │ │ strb w4, [x5]

From the profiling it looks like a lot of time is being spent on the if condition and so ensuring the if condition is optimized is important. Under massive parallelism likelihood of getting the lock is pretty less so the if condition will always evaluate to true accordingly we should set the hint of if condition to likely()

likely()

Elapsed time: 38.2878 s

83.58 │4c:┌──b.ne 6c

8.90 │6c:└─→strb w2, [x4]

Based on the analysis it is observed that overall there is some % saving that eventually is also confirmed by the execution time. This hint did work in our favor and setting likely() was a good choice.

So sometimes making things explicit would just make things a bit easier and avoid differences based on compiler and architecture.

6. Enable 64 bit memory operations

Processing a 64 bits block at times is much faster than an 8 bits block. Most of the software would have this optimization but given softwares are meant to also run on 32 bits machines very likely said optimization is enabled only for 64 bits platforms using standard macros like _x86_64. Such a condition should also be enabled for ARM (__aarch64__) too.

Infact, the first thing users should do is search for all platform specific code flow and try to check if something similar could be done for ARM.

7. Hardware Instruction for specialized operations

There are certain compute intensive operations for which processors provide a specialized hardware instruction. Classic example is checksum. ARM provides support to use these instructions through its ACLE (ARM C Language Extension). GCC implemented a version of this extension and accordingly the said high level function could be used in the program that gcc would translate to specialized hardware instructions. Alternative is to directly write asm code but that is more complex and may not be portable across compiler and arm architecture.

C code:

crc = __crc32w(crc, *buf4);

Translate too:

f54: 1ac44842 crc32w w2, w2, w4

There are multiple such specialized instructions:

- Cryptographic: SHA, AES,

- Random Number Generation

- Direct Rounding

- Floating point handling

- Memory barriers are related like data barriers, instruction barriers, etc…

- Some scheduling/interruption hints.

- Swap of data.

- Prefetch data/instruction memory.

- ….And more data processing intrinsics.

8. Improved atomics support

Use of atomics variables are now becoming an inherent part of new generation software. With C+11 officially supporting atomics and associated performance advantage make it an optimal choice. ARM implements atomics using the traditional way that involved load-store combinations that often lead to a small loop with slightly longer instruction code. Starting ARM-v8.1 ARM introduced LSE Large System Extension that replaces the atomic operation to single instruction with better latency.

If software doesn’t support atomics then explore if atomics could be used for operations. If software already uses atomics then re-review if the existing atomics usage is optimal like using compare-and-swap is preferred alternative to exchange as former will bail out if the load evaluation is -ve. Enabling LSE may benefit some of the cases. One can also study the overall impact and accordingly make it the default compiling option.

Also, ARM defines memory semantics for most instructions (including new one) and gcc does a good job in emitting an optimal instruction in some cases.

Store to atomic

std::atomic<bool> lock_unit{0};

void func() {

lock_unit.store(true, std::memory_order_seq_cst);

lock_unit.store(true, std::memory_order_release);

}

Translate to:

on ARM: (Note: default strlrb has release semantics)

stlrb w1, [x0]

stlrb w1, [x0]

on x86: (Note: seq_cst emit exchange operation and normal store emits simple move (not flushing the write-buffer)).

xchg al, BYTE PTR lock_unit[rip]

mov BYTE PTR lock_unit[rip], 1

9. Use of SIMD/NEON for parallelism

All modern generation processors support SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data). x86 refers to it as SSE4.x support. ARM refers to it as NEON support. Idea is to execute a certain instruction on a vector of data and emit another vector of results.

ARM offers support for accessing NEON instruction either through assembly instructions or using NEON library support in C/C++. It supports a wide variety of load/store instructions that allow loading x bits of data from memory in interleaved fashion into registers and instructions to process and eventually store this interleaved fashion data in parallel.

NEON is widely used with signal/image processing kind of application but depending on use-case other applications too could exploit the massive parallelism it has to offer.

Conclusion

We saw some possible optimization aspects that developers can explore inorder to get optimal performance for software running on ARM. If all these aspects are adapted correctly then performance would be on par/better than other architectures that software support. Infact, some of the softwares like MySQL scale optimally on ARM beating x86 by significant margin despite having lesser compute power (but same number of vCPUs).

If you have more questions/queries do let me know. Will try to answer them.